User Stories Gone Wild!

Posted by Chris Sterling on 03 Jan 2009 | Tagged as: Acceptance Testing, Agile, Architecture, General, Leadership, Product Owner, Scrum, Software Architecture, User Stories, XP

The thought of less documentation is appealing to many in the software industry. Reducing the specificity of our requirements can have tremendous value but some go too far. One of the big myths about Agile software development is that Agile means no more documentation. This was not the purpose of the Agile Manifesto value “Working software over comprehensive documentation”. The ideas was that only the documentation that supports the creation of working software should be created. There are many reasons for software to have documentation:

- Maintainability

- User manuals

- Training

- Communication

- etc…

Since the idea of Agile software development is not to remove all documentation from software delivery then what is the right amount of documentation? Of course, the answer is it depends but we won’t leave it at that. This article will focus on one area of documentation and that is specifying what users want.

User stories were popularized by Mike Cohn with his book “User Stories Applied”. Many people do not read and take in all of what is provided in Mike’s book before using user stories to capture user desired functionality. Instead they may be introduced to it on the Internet, through a seminar, or in training. The appeal of user stories is they are short statements that are easy to write and fit on 1 index card. The problem, as Ron Jeffries explains it in his article “Card, Conversation, Confirmation”, is the statement written on an index card is not enough information for the development to implement without providing some clarity through conversation with someone who represents the user’s desires. So the first way that user stories “GO WILD!” is:

Stakeholders expecting that a statement written on an index card is enough for the team to implement what they desired in the software

And this can be more generalized as:

User stories inappropriately used and becoming just bad specifications

Development must have conversations with people knowledgable about the user story domain to clarify the desired functionality. And as Ron rightly describes, conversations may be supplemented with documentation when needed. This could be in the form of an user interface design, usability study, business rules, acceptance tests, and any other format necessary for the development team to implement the user story satisfactorily. During the conversation new understanding and clarity of the user story specifics will be drawn out. The next way user stories “GO WILD!” is:

Acceptance criteria (or “Confirmation” as Ron puts it) for the user story is not captured and many times forgotten during implementation

It is important that the development team and domain experts write down important nuggets of knowledge about the desired functionality. This could be as simple as writing it down as bullet points on the back of the index card or creating skeletons of acceptance test cases.

Sometimes teams come across user stories that seem either too ambiguous or potentially mammoth in size. There are some great indicators in the user story text that I have found over the years while working with them over the years. Here are a few ways that user stories “GO WILD!” along with ways to deal with them when they do:

Using conjunctions within the user story statement

Whenever I see an “and” or “or” or “if” or “until” or… well you get the picture… this is an indicator to me that more than one piece of functionality is being described. This is an opportunity to split the user story into multiple user stories usually right where the conjunction was put in.

Describing too much about “how” to implement the user story

It has been common in my experience to see business analysts or technical writers creating user stories to support a Scrum Product Owner or stakeholder group in defining their desired features. You might see phrases such as “when they click on … button”, “drop down”, and “using Excel” which are specific about the “how”. In the past, these people were asked to describe the functionality so it was clear for programmers to code and testers to verify. Now we are asking them to write user stories that describe “what” the user wants and not “how” to implement it. This is a problem since they have used the “how” to make clear requirements for the development team to implement. Agile teams are expected to take more responsibility in defining “how” the software is implemented. This includes providing their input on specifying and designing the software. Many times I have seen specification of features get simplified or enhanced through the conversation between development team and domain experts. We want this to occur more often since these interactions will increase software features delivered and improve the product for its users.

Can’t describe the value provided to the user for the desired functionality

There has been more than one time that I have asked “why are we implementing this user story” and was not provided a satisfactory answer. I may have gotten an answer like “because it is defined in the requirements document”, “because it was prioritized high”, or “because the CEO wanted it”. All of these may be good enough reasons to implement the functionality but it is less likely that the development or domain experts will implement it masterfully given the lack of understand around what the user wants to do with this functionality. Understanding how a user story fits into the bigger picture is important since it will enhance the conceptual integrity of the software overall. When software is implemented by generating many disconnected components and integrating them together into a cohesive package the software tends to become inconsistent in its usage with lots of hidden but potentially useful functionality. Ask yourself when writing a user story why would the user want this functionality. You can use the user story template:

As a [user role] I want to [do something] so that [I gain some benefit or value]

By address the “so that” clause you will provide more understanding of how the functionality fits into the larger picture. Or you may find out that it is not useful at all. In that case, you can throw it away and work on something of more value to your users.

Writing technical user stories in which the value is not understood by the Product Owner or stakeholders

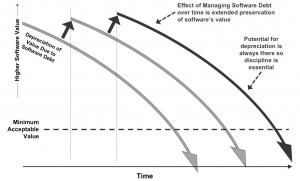

Technical user stories tend to get deprioritized since they are not easily assessed for value by most non-technical people. I have found that it is essential to describe why we have new technical needs or what the cost of not addressing a system’s quality attribute such as scalability could be. I have written an earlier post on this regarding a term coined by Mike Cohn called “abuse stories”. The idea is to capture the cost of not addressing an architectural or infrastructure need by describing it from an abuser of the software’s point of view. Writing technical needs in a user story format is not necessary but may be helpful while building trust between the development team and stakeholders. Sometimes project stakeholders believe that time and money is getting wasted on technical perfection. By writing the abuse story a development team can show that these technical needs are not just wasted efforts but provide value to the software. It is hoped that over time a team can just let their Product Owner or stakeholder group that there is a technical need that must be prioritized before particular functionality should be implemented and that will be enough.

Now that you know some ways that your user stories can “GO WILD!” it is time to tame those user stories so that your software can be the best it can be. Happy story writing! And, oh yeah, happy new year 2009!